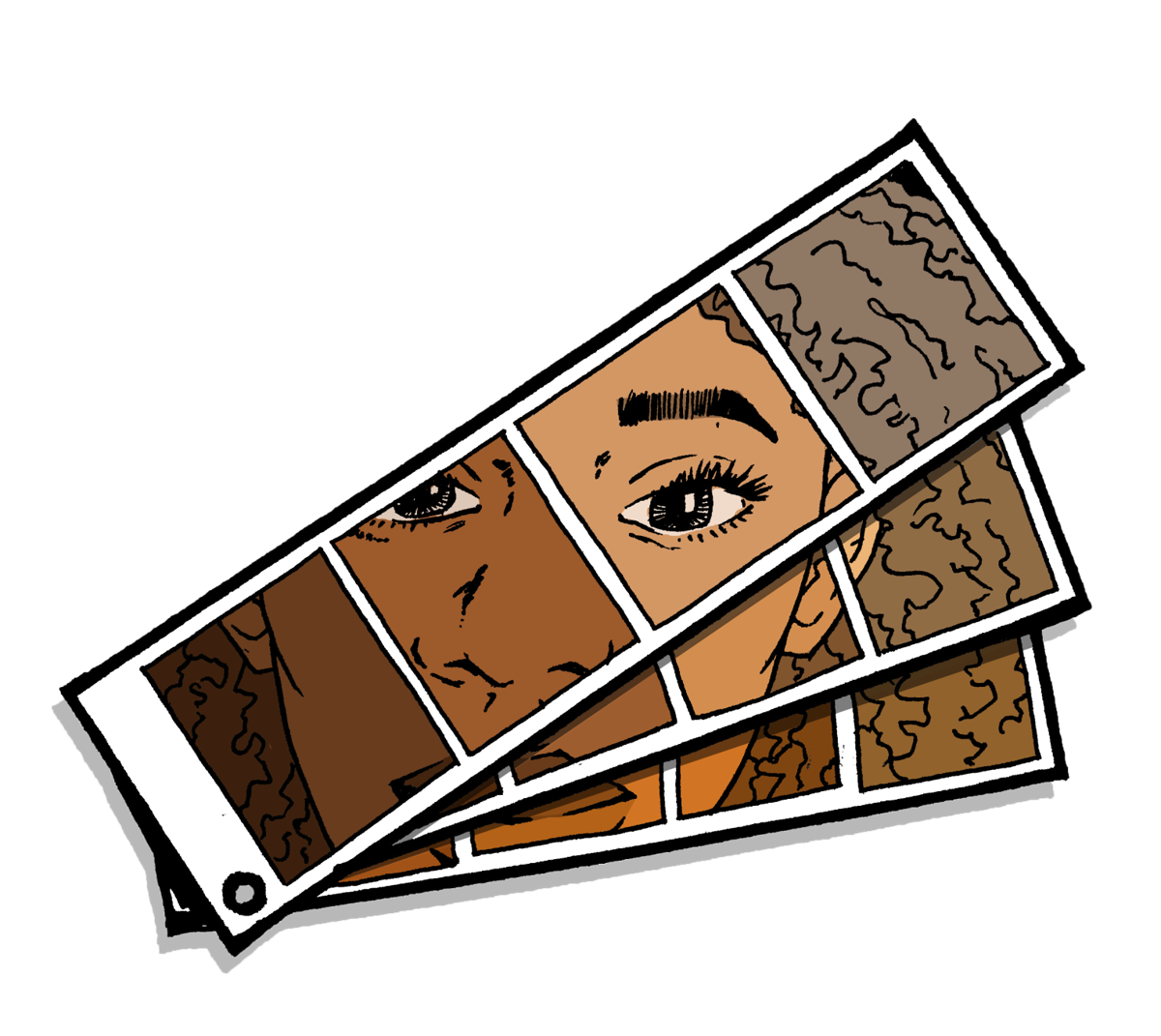

In digital spaces across the internet amid all the rallies for racial justice, there has been a sub conversation surrounding colorism. Colorism is defined as the prejudice of skin color within the same race. It is prevalent not only in African American culture but Asian cultures, South Asian cultures, Caribbean cultures and many more across the globe. The conversation revolves around the same thing: anti-blackness and the idolization of lighter skin. The bias that darker skinned people face within their own communities is an enigmatic burden to bear that can and should be dismantled. The act of challenging your own anti-black ideals subconscious or not is an act of decolonization that in my opinion is necessary if we want everyone to be truly equal.

It is without a doubt that you have witnessed colorism at work before. Colorism is adults telling young children to avoid the sun for fear of “being too dark”. Colorism is favoring one child over another for having lighter skin. Colorism is “They are pretty for a dark skinned person”. The distinction between colorism and racism is again that this happens within respective communities and not from someone outside of the community. Colorism is prevalent in everything, from hiring practices (favoring lighter skinned candidates) to the skin lightening industry becoming a $23 billion dollar business. The reality is darker skinned people are made to feel shame in something they cannot control.

There are extensive first-person accounts out there, but I’d like to highlight someone who has both talked and written about her experience.

Peou Tuy is an author and spoken word poet, she has survived through the Khmer Rouge as an infant and came to America as a refugee, living her life as a Khmer American. She is a darker skinned Asian woman and has faced colorism her entire life in the Khmer community. Here is a poem she wrote from her book, Khmer Girl titled “Bleaching My Skin”.

I hate her even in my sleep

dream I sharply slice her off

new fresh layers of white skin grow

I am forced to live with her

the sight of her makes me vomit

I consistently tell her she is too dark to be on me

but she insists it is not her fault

this color-haterism thing is biologically inherent

I buy

lightening cream

whiten her off my face

praying it will dry her out

shedding off layers after layers after layers

In showers

I turn the dial to boiling hot

in order to burn her to death

from my face to my neckarmscheststomachbackbuttocksthighslegsfeet

I harshly scrub her off with a coarse cloth

dipped in sodium lauryl sulfate

burning her firey red

I hate her!

I hate her!

I hate her!

Bitch! You desrve it!

Peou also speaks of her experience here. Some notable quotes from the interview:

“I felt horrible, I was told constantly by Khmer communities and people on the street ‘Oh she’s so dark!’ My parents would say ‘Yeah she’s the darkest one.’ or ‘Why don’t you wear this color, it looks better on you because you’re dark.’ and I felt like I was not worthy enough to live, I felt like my dark skin was a sin, I was told that every day.”

“As a child you get traumatized by that, thinking light skin is a better and the more light skinned you are the more successful you may become. I was very upset with the Khmer communities and my parents for a long time.”

“I felt like I had to compensate for my skin color.”

In addition, she describes how her brothers, also dark skinned, never got the same talks adding on to the intersectionality of the colorism issue:

“Women are meant to be elegant and porcelain-looking and light and pure and smooth, with men it’s a little bit different, sexist I would say, their skin color didn’t matter.”

I’d like to make the distinction, no one is saying that light skinned people do not face discrimination or racism, but we are saying it is imperative to recognize how the societal hatred of darker skin is hurting your community and how your actions can further normalize this behavior.

Let’s talk about history for a moment. The roots of colorism in America is nearly identical to the Caribbean. In both cases, the class stratification starts with enslavement and colonization. A social hierarchy purported by the White ruling class: putting whiteness at the top, blackness at the bottom, and mulattos (A mix of European + Black or Caribbean heritage respectively) somewhere in the middle based on perception. You can listen more about colorism in the Caribbean from Frances Robles here. This post will be focusing on colorism in America.

In the study “Genesis of U.S. Colorism and Skin Tone Stratification: Slavery, Freedom, and Mulatto-Black Occupational Inequality in the Late 19th Century” written by Dr. Robert L. Reece it was found in the U.S., that colorism has been prevalent both during and after slavery, providing Mulattos greater opportunities than their Black counterparts. Dr. Reece delves on many significant points. He sets the stage with that which we should already know:

“Research shows lighter skinned Black Americans outperform their darker skinned counterparts in income (Goldsmith, Hamilton, & Darity, 2006, 2007), education (Branigan et al., 2013; Monk, 2014), health (Diette, Goldsmith, Hamilton, & Darity, 2015; Monk, 2015); receive shorter prison sentences (Blair, Judd, & Chapleau, 2004; Viglione, Hannon, & DeFina, 2011); and are perceived as more attractive (Reece, 2016).”

Colorism permeates every aspect of life, it is something dark skinned people don’t have the privilege of ignoring. Next, Reece goes into specifics about the advantages lighter skin provided during chattel slavery:

“Enslaved Mulattos received a number of advantages relative to their Black counterparts. Because Whites generally thought Mulattos were sharper, more esthetically pleasing, and more capable of being “civilized”, they often offered them positions as house servants, away from the toils of field work, and afforded them the opportunity to acquire trade skills and other education that they could use outside of the plantation. Moreover, they were given significantly more freedom to move throughout and off the plantation (Frazier, 1930; Toplin, 1979)”

It is evident that this edge was no more than a happenstance because the White ruling class decided Mulattos were more “valuable”. However, dismissing the existence of this privilege is ignoring the barrier that holds back the darker skin people in our community. Similarly, how it is true that light skin people can face racism but can benefit from colorism (instead of being hurt by it), Dr. Reece talks of how being enslaved had varying degrees of effects on Black people vs Mulattos:

“Legacy of slavery is negative and significant for both Mulattos and Blacks, meaning both suffered lower occupational status as the proportion of slaves in 1860 increased, but the magnitude is much stronger for Blacks than Mulattos. This supports the primary hypothesis, suggesting although Mulattos and Blacks both suffered the negative effects of slavery, Blacks seemed to have suffered much more in the long term.”

“Literacy in 1860 is positive and significant for Mulatto occupational status, which means Mulattos in counties where they could read and write in 1860 had, on average, higher occupational status in 1880. Conversely, literacy in 1860 is nonsignificant for Blacks. This is evidence the preference for Whiteness that began during antebellum slavery allowed Mulattos to leverage their favorable color to capitalize, however limitedly, on opportunities that Blacks may not have been able to access. While this did not completely shield Mulattos from the negative effects of slavery, it offered a buffer to soften the effects relative to Blacks.”

Occupational status is arguably the most important aspect colorism could negatively affect in 1860. Despite the immoral connotation that your value is determined in how productive you are, in the US having the ability or skills to work to attain wealth is viewed as an asset. This disparity in who had the opportunity to advance has greatly shaped our workforce today, from hiring practices to wage gaps. While I was researching I began to ask myself, “Why feed the hate, if already so much of the world is against Black people, no matter skin tone? Why would discrimination within the same community continue to grow?” The next two excerpts help me deduce a plausible explanation, both historical and present-day connections:

“However, I argue the transition from slavery to freedom resulted in more than simple emulation in the case of Blacks and Mulattos. Instead, the boundaries between the two groups may have strengthened. Wimmer (2008) offers a theory of ethnic boundary formation that may be useful for explaining this possibility. He argues actors emphasize ethnic boundaries when they are incentivized to do so. In places where slavery was more prominent, Mulattos may have been incentivized to practice social closure strategies to strengthen the boundary between themselves and their Black counterparts.”

“…people receive social favor in proportion to their position on a sliding scale of visible Blackness. The “more White,” “less Black” a person looks, such as lighter skin, thinner noses, thinner lips, and straighter hair, the more White in-group benefits they receive, lifting their social position above their “Blacker” counterparts. Moreover, when a group—Black people—is forced to acknowledge the supposed superiority of a group higher on the social hierarchy—White people—they may also offer them preferential treatment, explaining why Black people also tend to favor lighter skinned people.”

We no longer live in the 1880s. There have been tons of strides made since that time, but alas the work is far from done. Acknowledging that colorism is alive and thriving today is necessary. Our standards for beauty on a societal level are European. Due to colonization, this is on a global scale, which is partially why colorism happens worldwide in a variety of different cultures. In the second quote, Dr. Reece pinpoints the heart of the issue of colorism: the social favor based on a light skinned person’s likeness to whiteness. Black features should not be seen as “unattractive” or undesirable. Whiteness should not be the standard for beauty. Colorism extends and negatively affects the very livelihood of darker skinned Black Americans. This is what is meant when people say “light skin privilege.” Whether you [in this case a light skinned person] knowingly or unknowingly benefit doesn’t matter. You do. You also can choose to carry on and enable colorism to discriminate or be conscious of the fact and strive to create more equal situations. We are amid a deep cultural shift, and so I pose to you: call colorists out and advocate in your daily life to unlearn these micro discriminatory habits that have macro effects on darker skinned people.

Ultimately his study came to an important conclusion:

“These results not only deepen our conceptions of early colorism by demonstrating it is indeed connected the circumstances surrounding chattel slavery, but they also offer insight into some of the specific antebellum mechanisms that created the post-Emancipation gap between lighter skinned and darker skinned Black Americans. Most notable is probably the differential effect of slavery on Blacks and Mulattos. Although a variety of sources documented Mulattos’ preferential treatment as slaves, until now we understood little about how privileged treatment translated into post-slavery social outcomes, empirically or theoretically. However, the positive effect of slavery on inequality and literacy Mulatto occupational status support the premise that the preference for Whiteness thesis may feed into boundary formation processes that allowed Mulattos to maintain their advantageous position over Blacks even as both suffered from the antebellum system.”

I encourage you all to read Dr. Reece’s work. They are well researched and provide insight into topics like Colorism that are not as widely explored by other academics. I personally plan on reading “The Gender of Colorism: Understanding the Intersection of Skin Tone and Gender Inequality” next, which was written this year.

History is the background of this painting, but as we approach the metaphorical foreground where is the situation now? As it is with most 21st century issues, capitalism comes knocking. Companies like Unilever profit off of dark skinned people’s insecurity, which as I’ve demonstrated is perpetuated on a societal level. Just this past June Hindustan Unilever has come under fire amid the renewed racial justice protests. Their product “Fair and Lovely”, a lightening cream that has been on the market since the 1970s is being scrutinized for its name as well as it’s use. Unilever has since changed the name to “Glow and Lovely” but the concoction remains the same, lightening people’s skin tone. Johnson and Johnson will rename some products to stop the emphasis on “fairness” as well as discontinuing some lightening creams. Right before 2019 came to a close two non-profits garnered 23,000 signatures asking Amazon to discontinue it’s participation in selling skin bleaching products. Surprisingly, Amazon listened. Again, it should be known that the skin-lightening industry was on track to becoming a $23 billion dollar industry. Skin lightening or skin bleaching is not considered safe by any means by the FDA, yet these products continue to be made and stocked on shelves. Products that hurt people on both a psychological(the idea that one’s skin tone they are born with needs to be “fixed”) and physical level should not flourish on the market.

Let’s recap. Colorism hurts melanated people, it can give lighter-toned people a sort of implicit advantage because of it’s likeness to whiteness. Colorism’s roots stem from white supremacy as well as anti-blackness. It exists on the individual as well as the institutional level. Once you acknowledge the existence of this colorism issue, what can be done? Well to start, educating yourself and others further about why dark skin is perceived as undesirable and acknowledging it is something people have no control over. Educate yourself on the implicit bias you may have and actively work to bring light to them and challenge them to level the playing field. The shade of someone’s skin tone should not be a factor when dating, hiring, deciding pay rate, or any other issue that is linked to someone’s livelihood.

Thank you for reading.

</a>

</a>